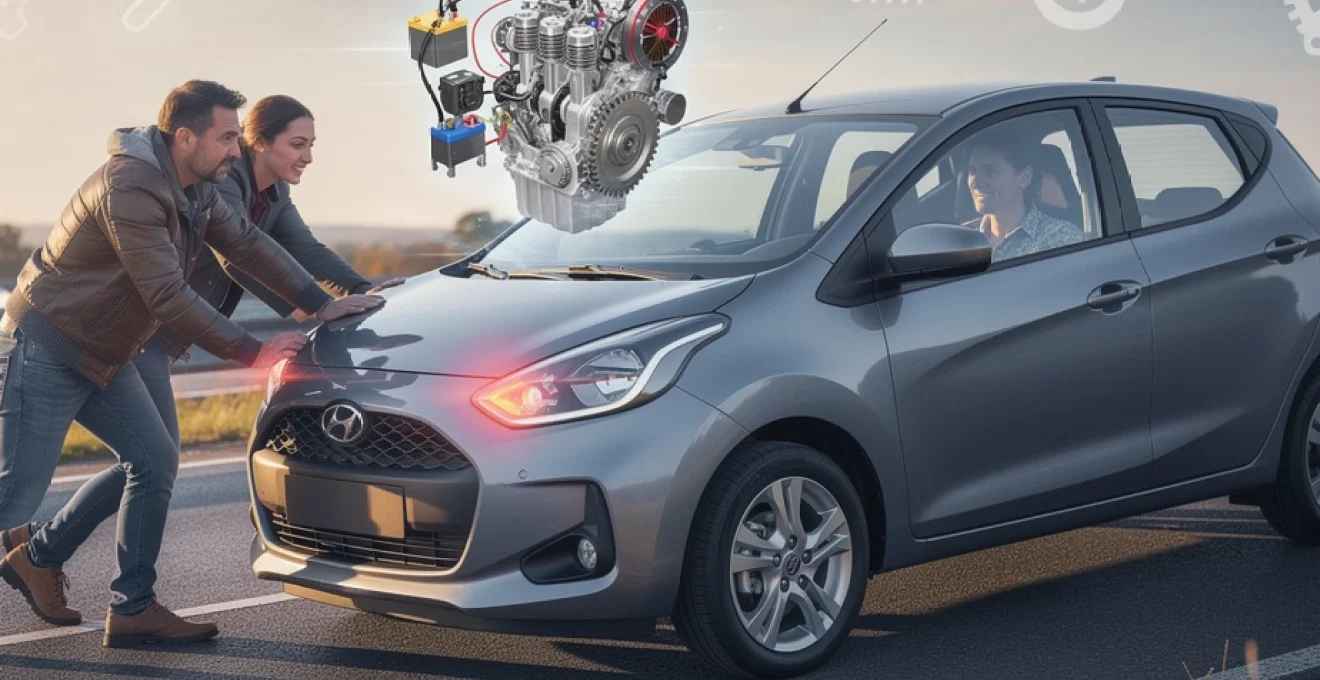

When faced with a completely dead car battery, the traditional click of the ignition key yielding nothing but silence can leave drivers feeling stranded and helpless. However, for vehicles equipped with manual transmissions, an age-old technique known as bump starting or push starting offers a potential lifeline that bypasses the electrical starting system entirely. This mechanical method harnesses the principles of engine compression and momentum transfer to breathe life back into a seemingly lifeless vehicle, provided certain critical conditions are met.

The effectiveness of bump starting depends on understanding the intricate relationship between your vehicle’s transmission, engine compression ratios, and electrical systems. Modern vehicles present unique challenges compared to their predecessors, with sophisticated engine management systems, electronic parking brakes, and advanced safety features that can significantly impact the success rate of this emergency starting procedure. Recognising these limitations before attempting a push start could mean the difference between a successful recovery and potential damage to your vehicle’s drivetrain components.

Push start mechanics: understanding engine compression and ignition systems

The fundamental principle behind bump starting relies on the mechanical relationship between wheel rotation, transmission gearing, and engine compression cycles. When you release the clutch while the vehicle is in motion, the kinetic energy from the moving wheels transfers through the transmission to rotate the engine’s crankshaft. This rotation forces the pistons through their compression strokes, creating the necessary conditions for combustion without requiring the starter motor’s electrical assistance.

Compression ratio requirements for successful engine turnover

Modern engines typically feature compression ratios ranging from 8:1 to 12:1, with higher performance vehicles often exceeding these figures. The compression ratio directly influences the force required to turn the engine over during a bump start procedure. Engines with compression ratios above 10:1 may require significantly more momentum to achieve successful ignition, particularly when the engine oil has thickened in cold weather conditions.

High-compression engines create greater resistance during the compression stroke, meaning you’ll need to achieve higher vehicle speeds before releasing the clutch. Diesel engines, with their typical compression ratios of 14:1 to 18:1, present particular challenges for bump starting and may require professional assistance rather than attempting this procedure. The increased compression also places additional stress on transmission components during the engagement process.

Ignition timing and spark plug function during push starting

The ignition system must function correctly for bump starting to succeed, requiring adequate voltage to fire the spark plugs at precisely the right moment. Even with a depleted battery, most modern ignition systems can function briefly using residual charge, provided the battery isn’t completely dead. The engine control unit calculates ignition timing based on crankshaft position, which becomes particularly critical during the irregular rotation speeds experienced during bump starting attempts.

Spark plug condition significantly affects bump start success rates, as fouled or worn plugs require higher voltages to create consistent sparks. Cold weather compounds these challenges, as spark plugs may struggle to ignite fuel mixtures efficiently even under normal starting conditions. Modern vehicles with individual ignition coils for each cylinder typically perform better during bump starts compared to older distributor-based systems.

Fuel injection vs carburettor systems in manual starting procedures

Electronic fuel injection systems rely on electrical pumps to deliver pressurised fuel to the injectors, creating potential complications during bump starting procedures. When the battery voltage drops below operational thresholds, fuel pumps may fail to generate sufficient pressure, resulting in lean fuel mixtures that resist ignition. However, many modern fuel systems include residual pressure that may support brief engine operation even with compromised electrical supplies.

Carburetted engines, though increasingly rare in modern vehicles, often respond more favourably to bump starting procedures. The mechanical fuel delivery system doesn’t require electrical power, allowing for more consistent fuel flow during emergency starting attempts. Understanding your vehicle’s fuel delivery system helps predict bump starting success rates and informs decisions about alternative recovery methods.

Engine management unit (ECU) response to alternative starting methods

Modern engine management systems monitor numerous parameters including crankshaft position, throttle position, and various sensor inputs to optimise engine performance. During bump starting, the ECU may receive conflicting signals as the engine

detects sudden, irregular crankshaft rotation driven from the wheels rather than the starter motor. In most cases this is interpreted simply as a low‑speed start attempt, but on some vehicles the ECU may delay fuel injection or ignition until it has synchronised crank and camshaft signals. If key security systems, immobilisers, or clutch/ brake interlocks are not satisfied, the ECU may block injection entirely, making bump starting impossible regardless of how fast you manage to roll the car.

Another important factor is system voltage at the ECU’s power supply pins. Many control units will shut down or enter a reset loop below about 9–10 volts, so a car with a truly dead battery may not respond to push starting at all. This is why some vehicles will fire instantly with only a small portable booster attached, yet refuse every bump start attempt. In borderline cases, briefly charging the battery or reducing other electrical loads (lights, heated screens, fan blowers) can give the ECU just enough headroom to manage a successful start.

Manual transmission requirements for bump starting procedures

Bump starting only works when there is a direct mechanical link between the driven wheels and the engine, which is why a manual transmission is essential for this method. The clutch and gearbox allow you to connect the rolling wheels to the crankshaft and generate the compression needed for ignition. In contrast, automatic gearboxes rely on fluid couplings and complex hydraulic control systems that cannot transmit low‑speed push forces in the same way.

Before attempting to bump start a car with a dead battery, you should confirm that the vehicle has a conventional manual transmission and a manually operated clutch pedal. Semi‑automatic transmissions, dual‑clutch gearboxes with electronic control, and automated manuals that require hydraulic or electric actuators often cannot engage a drive gear without adequate battery voltage. Even if you can physically select a gear, these systems may not allow true mechanical engagement, severely limiting push start success.

Clutch engagement techniques for optimal engine compression

The way you engage the clutch during a bump start has a major impact on both success and mechanical stress. If you simply “drop” the clutch pedal abruptly at low speed, the sudden load can cause the wheels to lock momentarily, especially on wet or loose surfaces. This not only reduces the chance of the engine turning over cleanly but can also shock drivetrain components, increasing wear on the clutch, gearbox, and driveshafts.

A more effective technique is to release the clutch progressively, much like you would during a smooth hill start. As the vehicle reaches around 5–10 mph (8–16 km/h), you quickly but not violently lift the pedal to the bite point, allowing the clutch to slip briefly while the engine begins to rotate. Once you feel the engine catching and firing, you immediately depress the clutch again to let the engine stabilise at idle without being dragged down by the car’s momentum. This controlled engagement balances the need for compression with the need to protect your transmission.

Gear selection strategy: second gear vs third gear performance

Choosing the right gear is another critical element of bump starting a car with a dead battery. Most technicians recommend using second gear on level ground because it offers a good compromise between mechanical leverage and smoothness. First gear multiplies torque so much that the engine may resist turning and the tyres are more likely to skid, while higher gears may not transmit enough force at low speeds to compress the cylinders effectively.

Third gear can be useful if you are rolling down a steeper hill or achieving higher speeds before clutch engagement. In these conditions, third gear reduces the engine’s initial RPM spike and provides a more progressive connection, particularly helpful in high‑compression engines that are otherwise difficult to turn. As a rule of thumb, you should select the gear you would normally use at that vehicle speed in everyday driving. This keeps the engine speed in a realistic range and reduces the risk of over‑revving as the engine fires.

Flywheel and starter motor bypass mechanisms

During a normal key start, the starter motor engages a small pinion gear with the flywheel ring gear to spin the engine. Bump starting bypasses the starter motor completely by driving the flywheel from the opposite direction in the powertrain: torque flows from the wheels, through the driveshafts and gearbox, to the clutch and then to the flywheel. The heavy mass of the flywheel helps smooth the irregular push forces, storing rotational energy in the same way it does during normal engine operation.

Because the starter motor is not involved, a car with a faulty starter solenoid, worn brushes, or a seized starter can sometimes still be revived with a push start, provided the battery still has enough life to power the ignition and fuel systems. However, repeated harsh bump starts can stress the flywheel ring gear and clutch hub splines over time. If you find yourself relying on bump starting regularly, it is a strong indicator that the starter circuit or battery system needs professional diagnosis rather than continued work‑arounds.

Battery state assessment and electrical system diagnostics

Before relying on a bump start, it is wise to understand just how “dead” your battery really is. There is a big difference between a slightly discharged battery that struggles to turn the starter and a heavily sulphated or failed battery that cannot support even low current loads. A quick electrical assessment can help you decide whether bump starting a car with a dead battery is realistic, or whether you are better off using jump leads or calling for roadside assistance.

Even if you do manage to push start the engine, an unhealthy battery can leave you stranded again as soon as you switch off, or place excessive strain on the alternator as it tries to recover the lost capacity. For this reason, technicians often treat a flat battery not just as a momentary inconvenience but as a symptom that deserves a structured diagnostic approach. Understanding the state of charge, state of health, and presence of any parasitic drain can save you repeated emergencies.

Voltage testing with digital multimeters and battery load testers

A digital multimeter is one of the simplest tools you can use to assess whether bump starting is worth a try. With the engine off and the vehicle at rest, a healthy, fully charged 12‑volt lead‑acid battery should read around 12.6–12.8 volts across the terminals. Readings between 12.0 and 12.4 volts indicate partial discharge, while anything under about 11.8 volts suggests a very low state of charge that may prevent the ECU and fuel pump from operating reliably during a push start.

For a more detailed picture, a battery load tester can simulate the heavy current draw of a starter motor and monitor how far the voltage drops under load. If the voltage collapses rapidly below 9.6 volts during a 10‑second load test, the battery is likely sulphated or internally damaged, and simply driving after a bump start may not restore its performance. Think of this like checking both blood pressure and heart rate: open‑circuit voltage tells you about charge level, while load testing reveals the battery’s underlying health.

Alternator functionality during push start recovery

When you successfully bump start a car, the alternator immediately becomes the main charging source, working to refill the battery and support the vehicle’s electrical systems. If the alternator is weak or failing, however, you may notice dimming lights, unstable idle, or even stalling as electrical demand exceeds supply. In such cases, a push start may get you moving briefly but will not solve the underlying charging problem, and the battery will quickly discharge again.

You can perform a basic alternator check by measuring battery voltage with the engine running after a successful bump start. A properly functioning alternator typically raises system voltage to around 13.8–14.4 volts. If you see little or no increase compared with the engine‑off reading, or if voltage fluctuates wildly with engine speed and electrical load, the alternator or its regulator may be at fault. In that scenario, using a bump start to limp to a workshop is reasonable, but continuing to drive long distances without repair can leave you stranded far from help.

Starter solenoid and ignition switch circuit analysis

Sometimes the battery is not the real villain at all. If you turn the key and hear only a faint click, or nothing whatsoever, the problem may lie in the starter solenoid, relay, or ignition switch circuit. Because bump starting bypasses the starter motor’s need for high current, a car with a good battery but a failed starter solenoid can often be started by pushing, which can be very revealing from a diagnostic point of view.

Technicians often use a simple test lamp or multimeter to verify whether voltage reaches the starter solenoid control terminal when the key is turned to the “start” position. If power is present but the starter does not engage, the solenoid or starter motor is suspect. If no power reaches the terminal, the fault may be in the ignition switch, a neutral or clutch safety switch, or associated wiring. Knowing this helps you decide whether a bump start is a safe temporary workaround or whether electrical repairs are urgently required.

Parasitic draw detection using ammeter measurements

If your car repeatedly ends up with a dead battery after being parked, a parasitic current draw could be slowly draining the system. Modern vehicles normally exhibit a small standby draw—often in the range of 20–50 milliamps—to support alarm systems, memory functions, and remote locking. However, a stuck relay, faulty module, or miswired accessory can increase this draw significantly, flattening an otherwise healthy battery overnight or over a few days.

To check for excessive parasitic drain, an ammeter is connected in series with the battery negative terminal once the car has gone to “sleep” (which can take 10–30 minutes on newer vehicles). If the reading remains high, technicians then remove fuses one by one to identify which circuit is responsible. Addressing these hidden loads is essential if you do not want to rely on bump starting every time you leave the car parked. After all, push starting is a useful emergency tactic, not a sustainable long‑term strategy.

Vehicle-specific push starting compatibility and limitations

Not all vehicles are equal when it comes to bump starting with a dead or weak battery. As electronics and safety systems have become more complex, many modern cars simply will not start without a minimum voltage threshold being met. Keyless entry systems, electronic steering locks, electric fuel pumps, and brake or clutch interlocks may all require stable power before the ECU even allows fuel injection to begin. In such cases, you might roll the car for hundreds of metres without a single sign of life.

Cars equipped with automatic or semi‑automatic transmissions, electric parking brakes, or stop/start technology are often poor candidates for push starting. Some manufacturers explicitly warn against bump starting in the owner’s manual due to risks to catalytic converters, timing chains, or emission control systems. If your car uses an electronic handbrake or requires the brake pedal to be depressed for the ignition to activate, low battery voltage can prevent these prerequisites being met, making bump starting impractical or unsafe.

Older, mechanically simpler vehicles—especially those with manual gearboxes, cable‑operated throttles, and minimal electronic management—tend to be the most forgiving. Classic carburettor‑equipped cars, for example, often respond well to a gentle push and a well‑timed clutch release. Nevertheless, even with these vehicles you should consider the condition of your clutch, gearbox mounts, and driveshafts before repeated push start attempts. What seems like a clever shortcut today could accelerate wear that becomes an expensive repair tomorrow.

Safety protocols and legal considerations for roadside push starting

While it is tempting to focus purely on the mechanics, safety must come first whenever you consider bump starting a car with a dead battery on the roadside. Moving a heavy vehicle manually introduces real risks to both the driver and any helpers, especially near live traffic. Loss of control on a slope, reduced brake assistance when the engine is off, and limited power steering can quickly turn a simple push into a dangerous situation if you are not properly prepared.

Before attempting a push start, you should always assess the environment: is the road flat, quiet, and well‑lit, or are you on a busy carriageway with limited visibility? In many cases, it will be safer to move the vehicle to a secure location and call for professional breakdown assistance rather than risking injury. Remember that when the engine is not running, brake servo assistance and power steering are unavailable, so stopping distances increase and steering requires much more effort, particularly at low speeds.

Legal requirements also come into play. On public roads, the person in control of the vehicle must hold a valid driving licence, and the car itself must be taxed, insured, and roadworthy. Push starting on a live motorway or in fast‑moving traffic could be interpreted as dangerous behaviour and may attract police attention, especially if you are obstructing lanes or putting others at risk. In some jurisdictions, failing to use warning triangles, hazard lights, or reflective clothing when working around a broken‑down vehicle can also have legal consequences.

From a practical standpoint, clear communication between the driver and pushers is vital. Agree on signals for starting, stopping, and aborting the attempt before anyone touches the car. Use hazard lights, and where safe, place a warning triangle at the recommended distance behind the vehicle to alert approaching drivers. If at any point you feel that the risk outweighs the benefit—perhaps due to poor weather, darkness, or heavy traffic—it is wiser to step back, secure the scene, and wait for professional help than to press on with an unsafe bump start.

Alternative emergency starting methods: jump leads and portable power packs

Given the mechanical and safety challenges involved, it is worth asking: is bump starting really the best option for reviving a car with a dead battery? Often, the answer is no. Jump leads and portable power packs provide more controlled and less physically demanding ways to start a vehicle, while also giving the battery a better chance of recovering enough charge to power essential electronics. These methods are particularly valuable for vehicles that cannot be push started at all, such as automatics and cars with complex electronic systems.

Traditional jump leads require access to a donor vehicle with a healthy battery. By connecting the positive and negative terminals correctly and allowing a few minutes of charge transfer, you can usually provide enough current to crank the engine in a normal way. This approach ensures that the ECU, fuel pump, and ignition system all receive proper voltage levels, improving the likelihood of a smooth start and avoiding the shock loads associated with bump starting. However, improper use of jump leads can damage sensitive electronics, so it is essential to follow the manufacturer’s instructions and connect the cables in the correct order.

Portable power packs, sometimes called jump starters or booster packs, have become increasingly popular as compact, battery‑powered rescue devices. They can be stored in the boot and used without needing a second vehicle, making them ideal for solo drivers. Many modern lithium‑based boosters are capable of delivering high cranking currents despite their small size, and often include built‑in protection against reverse polarity and short circuits. Used correctly, a power pack can start a car with a flat battery in seconds, without the need to push or find a hill.

In some situations—such as a deeply discharged, aged, or physically damaged battery—even jump leads or a booster may only provide a temporary reprieve. If you notice that the engine turns slowly despite a boost, or that the car will not re‑start after a short stop, it is likely that the battery or charging system needs replacement or repair. In these cases, arranging professional assistance or mobile battery fitting can be more cost‑effective and safer than repeated roadside improvisation.

Ultimately, bump starting a car with a dead battery should be viewed as a last‑resort technique rather than a regular habit. Understanding how and why it works can help you make smarter choices in an emergency, but pairing that knowledge with safer alternatives—such as carrying a quality booster pack and maintaining your charging system—will keep you moving with far less stress.